For two young men, hope had long expired.

Both were in their twenties when arrested. Both had only primary school education. Both were condemned by the highest courts of their lands.

One sat on death row in Jakarta, awaiting execution by firing squad. The other languished in Nigerian prisons, sentenced to hang.

They did not know each other. They lived on different continents. They spoke different languages.

Yet fate bound them by one final, terrifying certainty: the Supreme Courts had spoken, and death was the verdict.

Then came one more shared chapter.

Emmanuel Ogebe.

When the Law Had Closed Its Final Doors

For death row inmates, especially foreign nationals and the poor, legal battles rarely end in mercy. Appeals exhaust themselves. Files gather dust. Time hardens despair.

Emmanuel Ihejirika’s Story: 20 Years in Indonesian Hell

In early 2000s, “Emmanuel Ihejirika” was arrested in Bali, accused of attempting to smuggle heroin. He was initially sentenced to life in prison, but when his case reached a higher court, that life sentence was replaced with death by firing squad on an assumption that the forged Sierra Leonean passport he was carrying had serially been used to enter Indonesia so he must be a serial drug trafficker.

For nearly two decades, Ihejirika sat in Indonesian prison, his name appearing on execution lists. Indonesia’s death penalty for drug trafficking is notoriously harsh—in 2015 alone, 14 prisoners were executed, including 12 foreigners. In 2016, four more met the firing squad.

But Ihejirika’s case carried a deeper injustice: mistaken identity. Court documents showed conflicting information about who he truly was—charged as “Emmanuel O Ihejirika from Sierra Leone” when he was actually Nigerian. His lawyers argued he was convicted under a false identity, which under Indonesian law could constitute grounds for freedom.

When British humanitarians in Indonesia visited death row prisoners, they discovered Ihejirika among 21 Nigerians on death row. Four had already been executed. The case appeared closed, buried in legal finality.

Ogebe refused to accept that.

Sunday Jackson’s Story:

Punished for Surviving

In 2015, Sunday Jackson was a student and farmer working his land in Don village, Demsa Local Government Area of Adamawa State, when a Fulani herdsman named Buba Bawuro entered with his cattle.

A confrontation erupted. Bawuro, a Fulani herder armed with a knife, attacked Jackson, stabbing him multiple times.

Fighting for his life, Jackson managed to seize the knife from his attacker and, in the struggle, stabbed Bawuro in the neck.

The herdsman died.

Jackson was arrested and charged with murder—not manslaughter, but premeditated murder.

Despite his injuries and the fact that he had used his attacker’s own weapon, Nigerian courts strangely rejected his self-defense claim.

In 2021, he was sentenced to death by hanging. The court ruled he should have fled after disarming his attacker instead of fighting back – notwithstanding that he had been incapacitated by a stab to the leg and the assailant still wielded a stick.

Jackson spent five years awaiting trial and years more on appeals.

During those years, rather than succumb to despair, though resigned to his fate, he pursued education, earning a diploma while imprisoned. He had been too poor to complete secondary school and went into farming to sustain his family of three.

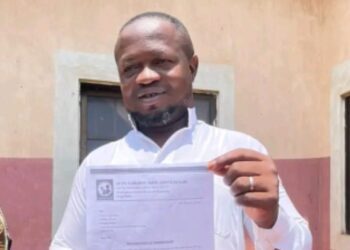

In March 2025, Nigeria’s Supreme Court upheld his death sentence.

Then Emmanuel Ogebe stepped up.

The father of the deceased attacker wrote a letter of forgiveness to the state Governor, pleading for Jackson’s pardon which Ogebe submitted. Still, the death sentence stood.

The Intervention

Indonesia: Fighting Mistaken Identity

Ogebe, a Washington D.C.-based international human rights lawyer, took on Ihejirika’s case pro bono.

More crucially, Ogebe built his case on the mistaken identity issue—arguing that Ihejirika had been wrongfully convicted under false information.

He pursued the case through Indonesia’s Supreme Court, navigating a foreign legal system with death as the alternative to victory.

He worked alongside the Nigerian Charge D’Affaires in Indonesia, Patricia Alechenu, and coordinated with the Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NIDCOM), led by Abike Dabiri-Erewa, who had visited Indonesian prisons years earlier as a member of Nigeria’s House of Representatives.

Nigeria: Exposing Judicial Failure

When Ogebe read about Jackson’s death sentence in February 2021, he flew to Yola to meet with Jackson’s counsel Francis Ogbe – provided by the Legal Aid Council because Jackson was too poor to afford his own lawyer. Reviewing the judgment on the spot, Ogebe immediately identified spotted constitutional violations: a 167-day lapse between the close of argument and judgment when Nigeria’s constitution mandates 90 days.

He took the case to international forums, including US & UK parliaments and the UN bringing Jackson’s plight to global attention. The case became a focal point in discussions about religious persecution in Nigeria, particularly after the U.S. re-designated Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern for severe religious freedom violations.

Even when Nigeria’s Supreme Court upheld the death sentence in March 2025, with only one dissenting justice arguing for Jackson’s freedom, Ogebe pressed on—pursuing clemency through Governor Ahmadu Fintiri of Adamawa State.

Two Christmas Eves, Two Miracles

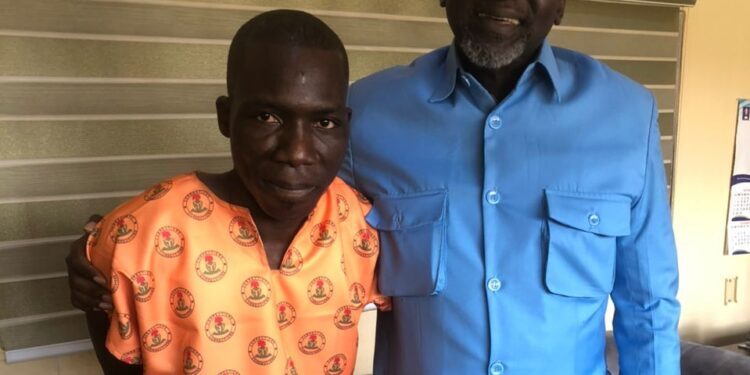

On December 24, 2023, Ogebe landed in Abuja airport from Jakarta—not alone, but with Emmanuel Ihejirika, a man who had spent 20 years under the shadow of a firing squad. After nearly two decades on death row, that journey marked his first drive toward freedom.

Exactly two years later—Christmas Eve 2025—history repeated itself.

Governor Fintiri signed pardon papers freeing Sunday Jackson under a Christmas clemency order landed at Abuja airport as a courier flew them down personally. Jackson, who had entered prison in his twenties, walked out in his thirties—alive, pardoned, free.

“They both drove down the same Abuja road to their freedom two years apart,” Ogebe reflected. “If that’s not divinely scripted, I don’t know what is.”

Beyond the Courtroom

What makes Ogebe’s story extraordinary is not just legal brilliance—it is persistence where systems fail, compassion where bureaucracy hardens, and faith where the world sees only paperwork.

He did not inherit powerful clients. He did not fight popular causes.

He fought for men society had already erased.

In two different countries. Under two different legal systems.

Against two irreversible death sentences. Against mistaken identity in Indonesia. Against a flawed self-defense ruling in Nigeria.

And he won. Twice.

A Lawyer of Last Hope

In a world where justice often favors the powerful, Emmanuel Ogebe has become something rarer: a lawyer of last hope—the one who steps in when all others have walked away.

For Ihejirika, Christmas 2023 meant life after 20 years of waiting for the firing squad.

For Jackson, Christmas 2024 meant freedom after a decade of punishment for surviving an attack and awaiting hanging.

For both men, Christmas will forever mean more than celebration. It will mean life restored.

Chains broken. Captives freed. Family reunited.

A road to freedom—driven twice, two years apart, guided by one relentless advocate.

And for history, it will record this truth: Twice in two years, Emmanuel Ogebe walked into death row—and walked out with life.

“A country that failed to stop mass murder nearly executed a man who survived one,” Ogebe said after Jackson’s release. His work continues advocating for judicial review, legislative clarification on self-defense laws, and compensation for those whose years were stolen by legal failure.

In 2025, he secured a small rehabilitation grant from the UN for Ihejirika. His last official act representing him for 20 years.

“However the freedom of Jackson is only the beginning and not the end.

The odious and repugnant precedent that goes against natural law, moral and substantial justice must be overturned. It defies science, logic and human nature. It is an advance mass death sentence on the Nigerian citizen in favour of foreign killers.

Jackson should never have spent a day in prison much less 11 years. He’s lost everything – his wife who remarried and then died and his home destroyed in a devastating Fulani attack. He’s lost 11 years of Fatherhood of a daughter he didn’t know existed till she was six and she has lost having a father for all her life.

Jackson may be free but the rest of us are not. This isn’t yet over.”