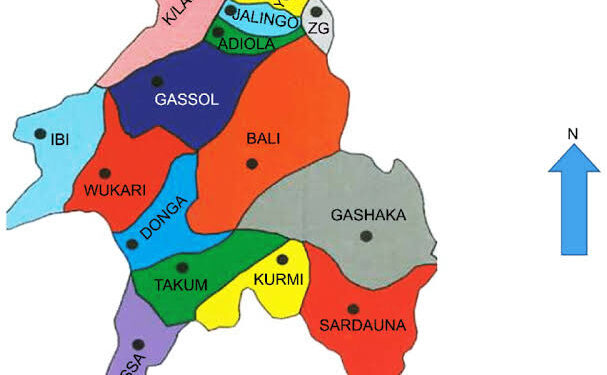

For decades, Southern Taraba has been the quiet engine room of Taraba State politics. But as the 2027 transition season gathers momentum, the region’s dominance is no longer subtle, it is unmistakable. And now, political watchers are asking: What if power continues to reside in Southern Taraba?

Across the three major parties, PDP, APC, and ADC, the strongest prospective contenders all appear to be emerging from the same axis. In the PDP, rising speculation points toward Senior Advocate of Nigeria, Damian Dodo, as a likely flag bearer. In the APC, Governor Agbu Kefas, already a Southern Taraba son, gives the ruling party little reason to look elsewhere. And in the ADC, conversations revolve around either Senator Emmanuel Bwacha may defect to join them and be the party ticket holder, or Danji SS, both natives of the southern zone.

If these permutations hold, Taraba could be heading toward a political reality similar to states like Benue, where one region has consistently held the governorship, and others such as Delta, Akwa Ibom, and Kogi, which have experienced long spells of power staying in one dominant bloc. The trend is not unusual in Nigerian politics, but in Taraba’s case, it could mark the first time all major parties converge their choices in one geopolitical zone.

Southern Taraba’s political weight is not accidental. The region is home to some of the state’s heaviest political actors, figures whose influence, networks, and resources have no clear parallel in the northern and central zones. Stakeholders such as the elder statesman Gen. Theophilus Danjuma, Chief Dr. David Sabo Kente, Senator Emmanuel Bwacha, Governor Agbu Kefas, and a rising class of technocrats and financiers have shaped the region into a formidable political bloc. Their reach goes far beyond party lines, often determining alliances, endorsements, and outcomes long before the ballots are cast.

Yet the question remains: Can other regions challenge this dominance? For now, the North and Central zones lack personalities with comparable political machinery or unified regional interests. Internal fragmentation, shifting alliances, and an absence of deep-pocketed power brokers have weakened their ability to produce a consensus candidate strong enough to break the southern grip.

Analysts argue that if Southern Taraba sweeps the 2025 nominations across all major parties, the state may witness a political pattern similar to other Nigerian states where zoning debates gradually lose relevance, replaced by the sheer force of political capital. It could either stabilize Taraba’s politics under an experienced bloc—or trigger new agitations for balance and fairness.

Either way, one thing is clear: the road to 2025 is already tilting heavily toward Southern Taraba. And unless the other zones produce a surprise contender with the influence to disrupt the current tide, the region may be on its way to extending its hold on power—reshaping Taraba’s political story for years to come.