BY KUNI TYESSI

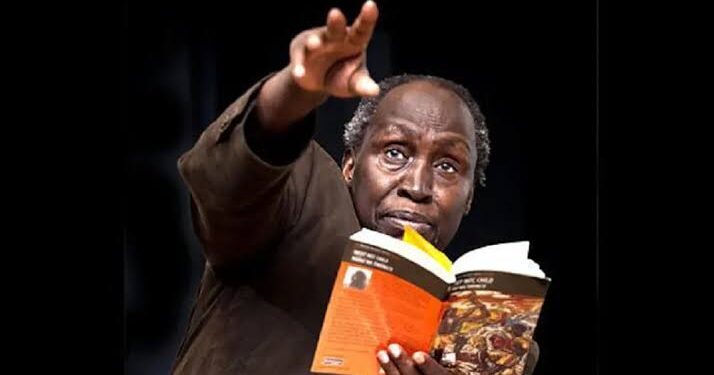

Since the demise of one of Africa’s best in the category of first generation writers, and in the world of literature- more so, one who helped give shape, direction and meaning to what African literature stands to be today, the social media has been inundated with his stand concerning the use and importance of language in literary writings and its potent ingredient in decolonizing the mind.

While it is true that, “Every writer is a writer in politics. The only question is what and whose politics”, as stated by Ngugi who dropped his ’English’/biblical name- James- to adopt that of his Gikuyu mother tongue by adding Wa Thiongo to Ngugi, and also to begin writing in it- it is important to hold the definition of language and its characteristics on the one hand, and the politics of it on the other.

Language as a complex system of communication consists of sets of rules, symbols and sounds which can be categorised into spoken, written and signs, with the primary aim to convey meaning and express thoughts, ideas and emotions which are all embedded in politics. This might be one reason the term ’Englishes’ have come to stay, thereby correcting the impression that English belongs only to native speakers when many nationalities have woven their mother tongue and all it encompasses around it.

As a result of East Africa’s exposure to colonialism and its attendant consequences such as land grabbing, clash between tradition and modernity, neocolonialism and the politics of independence; women’s rights/roles, as well as the effects of political instability amongst several others, Ngugi concluded that writing in the language of the colonizers was slave and defeatist mentality, thereby giving an upper hand to the colonial masters at the expense of the cravings of Kenyans to find their voice through indigenous languages.

In other words, the belief that once you can make a people speak your language, then they have been defeated and can be controlled politically and socio-economically held sway. While this might be true, the definition of language again suffices.

Recall that negritude writers such as Aime Cesaire, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Leon Damas, Abdoulaye Sadji and the siblings- Paulette Nardal and Jeanne Nardal who went through the fire of the French under the style of governance called ’Policy of Assimilation’ with the Assimilationist ideology been enthroned, also rebelled against their colonizers using the French language in the tactics called the politics of language to assert their African identity, challenge colonialism and the wounds of its protracted exposure, as well as promote black consciousness. Did their messages and the brutal forms they might have taken get to their colonizers? The answer is yes. Did it in any way change the perception of their colonizers towards them? The answer on whichever divide is debatable.

Little wonder, Nobel laureate- Wole Soyinka, in an opposite direction of negritude had come up with his own debate about the politics of language which was popularized around literary circles with the term, ’Tigritude’. He was of the opinion that tigers don’t announce their presence or traits, as they are known to simply exhibit them. In essence, the negritude writers could simply take the stance of tigers and not by mere announcement through their works. Announcement through their works was not enough, and cannot be if the same energy was (is) not portrayed in the promotion of their culture and system of governance even after independence.

Chinua Achebe, another African literary giant, arguably the father of African literature whose pen continues to write from the great beyond, seems to have agreed with Soyinka by writing in English- the language of the colonial masters. In his celebrated novel, “Things Fall Apart” which has been translated into not less than 33 languages around the world, he speaks about the Igbo socio-cultural setting in its naturalness before it was compromised by external invasions.

As a deeply-rooted Igbo man who even worked as a propagandist on the side of the Biafra army during the Nigerian civil war, Achebe believes that language is communication to a wider audience regardless of target.

What is the use of writing when the targeted audience cannot decipher the message? Should Nigerian writers no longer use the ISBN in the publishing of their books, but write for only local consumption? If ISBN should remain in use, and yes it should, due to a sizeable number of native Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba speakers in some African countries, has it addressed the issue of targeted audience in the expansion of literature, or like the sermon in the politics of language, such books should be for the native speakers even if not widely recognised? This is not to say that the dreams of having literature in our indigenous languages should be aborted, but in terms of lessons, it is to what end?

Despite being accused of writing only for the Igbos using the English language which he sometimes ’igbonizes’ as style to the admiration of his readers and critics alike, Achebe’s themes and characterization in his writings are never lost on the readers about the south eastern region of Nigeria. More examples of writers in this category include Cyprian Ekwensi, Elechi Amadi, Abubakar Imam, Gabriel Okara, Flora Nwapa, Adaora Lily Ulasi, Zulu Sofola and Mabel Segun to mention just a few. They all had love and respect for their respective cultures, but were not going to chase after the rat that ran out of a burning building without first quenching the fire.

Therefore, Ngugi definitely meant well for the African content, and the spirit that moved him towards writing about language and decolonizing the mind was positive in its conviction. However, writing literature in our indigenous languages is not the problem with us as Nigerians, or the cause of our multitude problems and backwardness. The problem is our mindset which indeed needs to be decolonized from the power of nepotism, corruption, religious bigotry and all the negatives that have held us down since independence.

In conclusion, pushing the blame to low patronage of indigenous Nigerian languages- and the debate that it will cure our colonized mindset of all the aforementioned negativities which are innately human and must be deliberately expunged, simply means we are not ready for constructive criticism and genuine change. While literature remains a mirror for the society, the cart must come before the horse. Until our mindset has been worked on, even if we commence, henceforth to write in our native languages, it will only be the case of a disease that had a name-change.