By Abdullahi O Haruna Haruspice

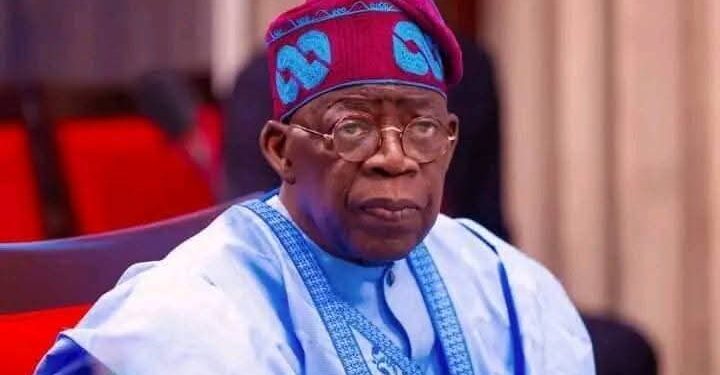

Nigerians can be forgiven for their skepticism. In a country where healthcare often means delay, despair, and debt, the idea of government-funded emergency treatment sounds almost too good to be true. Yet, under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s Renewed Hope Agenda, a potentially transformative initiative—the National Emergency Medical Service and Ambulance System (NEMSAS)—is quietly taking root.

NEMSAS, led by Coordinating Minister of Health Prof. Muhammad Ali Pate, promises every Nigerian free emergency care for the first 48 hours of hospital admission. It has already been piloted in institutions like Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), where emergency care has been integrated across multiple departments. Patients in dire need are no longer turned away for lack of funds—a long overdue departure from a system that has often placed money before medical urgency.

This is more than just free treatment. NEMSAS aims to overhaul Nigeria’s emergency response framework—from pre-hospital care to triage and stabilization. Hospitals must now properly document care, as only recorded interventions will be reimbursed. Symbolically, the initiative repositions healthcare as a right, not a privilege.

Its reach also extends beyond city hospitals. In Nasarawa State, the Rural Emergency Service and Maternal Transport (RESMAT) programme targets hard-to-reach communities, offering transport and emergency care to pregnant women and children under five. With tricycle ambulances and upgraded primary health centres, RESMAT seeks to address Nigeria’s dismal maternal mortality rates by removing both financial and logistical barriers to care.

International comparisons abound. Rwanda decentralized emergency obstetric care with great success, Brazil’s SAMU has become a lifeline across urban and rural regions, and India’s GVK EMRI processes hundreds of thousands of emergency calls daily. These models share common threads: scale, institutional clarity, and above all, political will. That President Tinubu has prioritized emergency care—despite tight fiscal reforms—suggests a commendable commitment to protecting vulnerable lives.

Of course, implementation is the Achilles’ heel. Nigeria’s bureaucracy can strangle even the best of policies. For NEMSAS to work, health workers must be trained, systems modernized, and corruption curbed. Awareness remains worryingly low, especially in rural communities. Civil society, religious leaders, and the media must amplify the message, while citizens must serve as watchdogs, reporting illegal fees or denied care.

There’s a deeper message here: emergency care could be a springboard for broader health sector reform. Unlike chronic care, which demands long-term investment, emergency medicine delivers quick, visible wins—saving lives and restoring public faith. The NEMSAS infrastructure—dispatch centres, triage protocols, record systems—could lay the groundwork for eventual universal health coverage.

The timing is also politically astute. With elections still distant and economic reforms underway, social programmes like this can build credibility and soften hardship. Critics may argue that 48 hours is too short. But in emergency medicine, minutes matter. Stabilizing a patient early often determines survival, and can prevent costlier complications.

Much credit goes to Prof. Pate, whose leadership has focused on delivery over rhetoric. The alignment between policy and on-ground implementation, seen in JUTH and Nasarawa, signals progress. But national scale-up will be the ultimate test.

What makes this initiative remarkable is its redefinition of state responsibility. In a country where citizens have long had to fend for themselves, offering free emergency care is a bold statement: that Nigerian lives matter, at least in their most vulnerable moments. If sustained, this could be remembered as the moment Nigeria began to repair its fractured social contract.

But for it to endure, the public must claim it. NEMSAS doesn’t belong to any party—it belongs to the people. It must not be wasted by disuse or eroded by cynicism. It offers, quite literally, a second chance—both for patients and for Nigeria’s promise of compassion in governance.