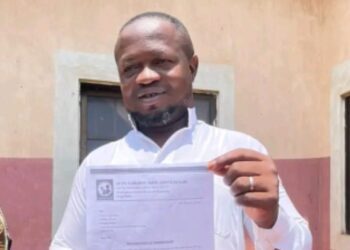

ABUJA – The high-profile criminal arraignment of Dr. Kabiru Turaki, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), was abruptly stalled on Wednesday at the Federal Capital Territory High Court, following a contentious hearing centred on a petition for the case’s transfer. Justice K.N. Ogbonnaya has subsequently adjourned the matter to 5th March.

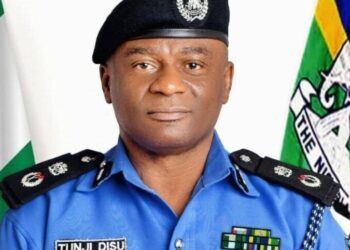

Dr. Turaki faces a one-count charge, filed by the Inspector-General of Police, of allegedly providing false information, an offence punishable under Section 140 of the Penal Code Law. The case, marked FCT/HC/CR/647/25, originates from a petition he reportedly sent to the police chief on 5th October 2022.

The scheduled proceeding marked the second unsuccessful attempt this week to secure the defendant’s formal plea. Initially listed for Monday, 26th January, the arraignment was deferred after Turaki failed to appear. Justice Ogbonnaya at that time issued a direct order for him to be present in court on Wednesday, 28th January.

Defying this judicial order, the senior lawyer was again absent. Prosecution counsel Usman Rabiu promptly applied for a warrant of arrest under Section 143 of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA), 2015. “The matter is for arraignment, my Lord. However, the Defendant has decided to stay away,” Rabiu submitted, urging the court to exercise its discretion.

In response, defence counsel S. Nasir informed the court that his client’s absence was due to a pending petition written to the Chief Judge of the FCT High Court, seeking the case’s transfer to another judge on grounds “to do with issue of confidence.” Nasir argued that justice is rooted in confidence and that a party retains the right to seek such redress, urging the court to dismiss the application for an arrest warrant.

The prosecution countered robustly, asserting that a criminal proceeding cannot be suspended merely because a petition has been filed against a presiding judge. Rabiu contended that allowing such a practice would enable defendants to frustrate trials unfavourable to them. He further emphasised that a party in disobedience of a court order cannot seek to be heard by that same court.

Court’s Ruling: Petition Does Not Stay Proceedings

In her ruling, Justice Ogbonnaya firmly upheld the principle that a petition to the Chief Judge does not legally halt ongoing proceedings. “There’s no law or judgement that says a Judge should stop proceeding because of a petition, except for a written instruction from the Chief Judge,” she stated.

The judge underscored the mandatory nature of court orders, stating that where an order for arraignment is made, a party must obey by appearing. “May the day never come when a party and a lawyer will choose a judge who will handle their case,” she remarked pointedly.

However, demonstrating judicial restraint, Justice Ogbonnaya revealed she had been instructed by the Chief Judge, whom she “hold[s] in high esteem and have respect for,” to respond to the petition. Consequently, she exercised discretion to adjourn the case rather than issue a bench warrant for Turaki’s arrest.

Background: A History of Legal Manoeuvring

The current stalemate follows earlier legal skirmishes in the case. On 3rd December 2025, the court had granted an order for substituted service of the charge on Turaki through his law firm. The defendant later filed a motion to set aside this order, which Justice Ogbonnaya dismissed on Monday.

In a strongly worded ruling that day, the judge wondered why a SAN, with lawyers representing him in court, could not be informed of a pending charge. “If court chases laymen with judicial bulala (cane), will court also chase a SAN with judicial bulala?” she questioned rhetorically. She concluded that the evidence clearly showed Turaki was aware of the charge, dismissing the motion as lacking merit.

While stopping short of an arrest warrant on Monday, she had unequivocally ordered: “The Defendant should be here on Wednesday, January 28, for arraignment.”

Legal Analysis: A Test of Judicial Authority and Procedure

This case presents a significant test of procedural authority and the balance between a defendant’s rights and the court’s imperative to control its processes. Legal experts note that while the ACJA provides mechanisms for recusal or transfer, these are typically not intended to be used as tools for absconding from lawful summons.

The prosecution’s argument against allowing petitions to stall trials touches on a fundamental concern for judicial efficiency and the potential for abuse. Justice Ogbonnaya’s ruling reinforces that the court’ timetable cannot be held hostage by unilateral administrative appeals, absent direct intervention from a higher judicial authority within the court’s hierarchy, such as the Chief Judge.

The decision to adjourn rather than compel attendance via a warrant reflects a nuanced application of judicial discretion, possibly prioritising a resolution of the confidence issue raised in the petition before proceeding substantively. It maintains procedural pressure on the defendant while allowing for administrative due process.

Looking Ahead: The March 5th Date

All parties are now expected to reconvene before Justice Ogbonnaya on 5th March. The intervening period will likely see a determination by the Chief Judge’s office on the transfer petition. The court’s patience, however, appears delineated. Should the defendant fail to appear at the next adjourned date without a formal stay or transfer order from the Chief Judge, the prosecution’s application for a warrant of arrest may meet a different outcome.

The case of Inspector-General of Police v. Kabiru Turaki (SAN) continues to draw significant attention, highlighting tensions between high-profile legal defence strategies and the judiciary’s mandate to ensure timely and unhindered justice. The developments on 5th March will be closely watched by the legal community and the public alike.